By Cecelia Puckhaber

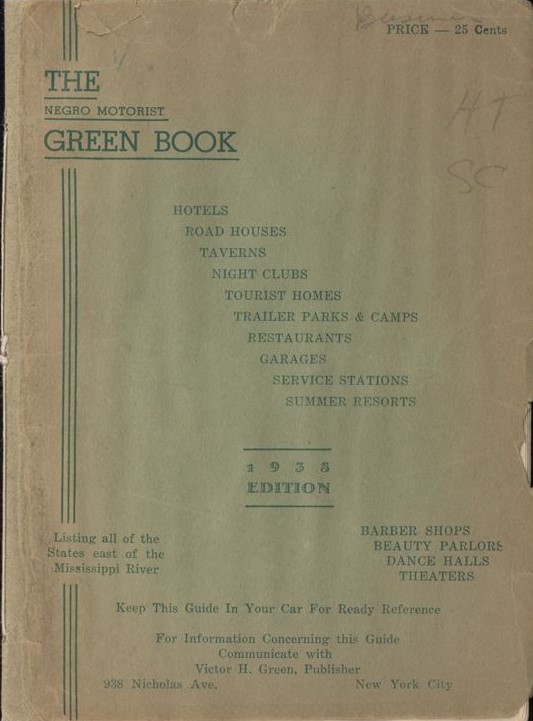

In the mid-20th century, during the era of Jim Crow, African American travelers often faced racial discrimination or violence from business operators at restaurants, hotels, or gas stations—even when passing through northern states. To address these concerns, Victor Hugo Green, a mailman from Harlem, New York, published The Negro Motorist Green Book in 1936.

Commonly referred to as “the Green Book,” it served as a guide for African Americans in search of businesses that were safe for them to visit in the city. The following year, Green began creating guides that included businesses in various states, asking “the Motorist and Business places for their whole-hearted co-operation to help us in our endeavor, by contributing ideas, suggestions, travel information and articles of interest.” It became a community project to provide travel information and list all the businesses welcoming African Americans to their establishments.

The Green Book Includes Connecticut Businesses

1938 Green Book, CT Section – New York Public Library. Used through Public Domain.

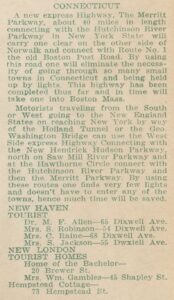

Connecticut joined the list of states included in the Green Book in 1938 after the development of the Merritt Parkway. The parkway, which is a little over 37 miles long, connects to New York’s Hutchinson River Parkway. It helped establish Fairfield County as a travel destination for many tourists, further connecting them to other places in New England. Green Book listings are concentrated in urban centers or thoroughfare corridors, such as the Merritt Parkway or (what is now) I-95. For example, the 1938 Green Book listed tourist homes and smaller hotels in cities such as Bridgeport, Hartford, New Haven, New London, Waterbury, and Stamford.

Many of the listings in the Green Book were located in African American communities and neighborhoods, providing not only lodging and dining options but also employment opportunities for those from the South hoping to find work in northern urban centers. The book played an important role in facilitating the Great Migration, when around six million people moved from the South to the Northeast, Midwest, and West between the 1910s and 1970s. As a result, more businesses welcoming African Americans began to open across the state. By the 1950s, the Green Book businesses expanded beyond the primary urban centers and could be found as far east as Pomfret, Connecticut, where a guesthouse called the Willow Inn was included in the Green Book from 1956 to 1966.

In total, 122 Connecticut businesses had listings in the Green Book, some of which were listed for several years between 1938 and 1967. The book grew to include hotels, tourist homes, restaurants, gas stations, clubs, and beauty parlors. What follows are just a few examples of Connecticut listings in the Green Book. Some of these establishments still exist today, even if they no longer serve the same purpose as they did when listed in the Green Book. Still, the establishments’ physical walls can preserve the stories of the business owners and the people they served during the era of the Green Book.

Fairfield County

Arcade Hotel, Bridgeport, Conn. – Boston Public Library. Used through Fair Use.

Bridgeport was home to various hotels, tourist homes, and a few Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) locations, especially in the Historic District. Among them was the Arcade Hotel, where the Arcade Mall currently stands on Main Street. During the civil rights movement, efforts to desegregate businesses led many hotels like the Arcade to open their doors without discriminating against customers. The hotel was listed in the Green Book during 1963 and 1967.

The YWCA set up a few locations across Bridgeport, the first opening in 1895 to support rural women transitioning into urban lifestyles. Initially, the YWCA was restricted to white women. African American women in Bridgeport then organized the Phillis Wheatley Branch in 1921 as a response to the racial segregation. The idea of ending segregation within the organization became more attainable through protests and the adoption of the “One YWCA Policy,” which worked to make the organization more inclusive. The policy required all YWCA members “to thrust their collective power towards the elimination of racism, wherever it exists.” By 1942, the Bridgeport YWCA desegregated and combined offices with the Phyllis Wheatley Branch into a facility located at 263 Golden Hill Street. It was first listed in the Green Book in 1949 as a hotel and would be included annually until 1962. The organization was committed to helping all working women in Bridgeport, regardless of skin color.

New Haven County

New Haven’s Dixwell Avenue had several options for African American travelers in terms of tourist homes, including Mrs. Mattie Robinson’s home. Robinson moved to New Haven from Virginia with her husband Samuel and became a widow in 1938. She was one of many women in Connecticut who independently ran tourist homes or boarding houses during the Green Book era. In the wake of her husband’s death, she may have opened her home to financially support herself, accommodating African American travelers from 1938 to 1947. The home was published in the Green Book for six of those nine years. The house and the other three documented tourist homes were on the same block as the House of Prayer for All People Church, which had a large African American community. The area was also in close proximity to other safe businesses, including shops, restaurants, and beauty parlors, all within walking distance.

Monterey Jazz Club was another building on Dixwell Avenue included in the Green Book from 1947 to 1967. Founded in 1934 by Rufus Greenlee, the establishment was a popular dining and entertainment destination for African American travelers passing through or staying in New Haven. It hosted a variety of famous singers and musicians, including Billie Holiday, Charlie Parker, and Ella Fitzgerald.

New London County

New London’s Hempstead Street became a center for African American life starting in the 1840s when abolitionist Savillion Haley began building homes to sell to Black families. One of those homes was Hempstead Cottage (73 Hempstead Street), which was eventually sold in 1926 to Sarah (Sadie) Dillon Harrison, Executive Secretary of the United Negro Welfare Council and Secretary of the New England Peoples Finance Corporation. With Edwin Henry Hackley, Harrison published the Green Book’s predecessor, Hackley and Harrison’s Hotel and Apartment Guide for Colored Travelers in 1930. The cottage was then rented out to African American travelers from 1938 to 1950. It is now one of fifteen sites included on New London’s Black Heritage Trail, which celebrates African American history through its ties to several buildings throughout the city.

Just down the street from Hempstead Cottage was the tourist home of Eva C. Whittle. Born in Virginia in 1888, Whittle moved north with her husband, Robert, ending up in New London by 1923. Robert died, however, so Eva worked as a house worker and offered rooms for travelers at two locations: one on Hempstead Street and one on Bank Street (now demolished).

The Impact of the Green Book in Connecticut

The Green Book documented various sites that significantly influenced the experiences of African American travelers. It helped exhibit Connecticut as a safe and appealing vacation destination by featuring a variety of services and resources that were welcoming to African Americans. Historically, however, Connecticut was not a completely safe place for Black travelers, which made the Green Book even more important in the state. Whether it was finding a secure place to stay, an accepting restaurant or business, or even a local community, the Green Book became an accessible guide for locations in Connecticut for 28 years.

Cecelia Puckhaber holds B.A. in history from Central Connecticut State University and was a digital humanities intern at CT Humanities.